Trigger Warning: This story contains a graphic portrayal of my mother’s struggle with anorexia nervosa. If you are currently struggling, or are recovered, you may find elements of this story triggering. Reader discretion is advised.

I’LL NEVER FORGET THE SOUND. The painful retching from behind the bathroom door. Most mornings I would wake up to the sound, as my childhood bedroom was just one wall away from the bathroom. When I was little, I had no concept of bulimia; no concept of throwing up at all, really. I would hear the strangled sounds emanating from the bathroom and panic would swell up inside of me; my mother was in pain, she was hurting. I should rescue her.

I would pound my small fists against the bathroom door, crying. I would ask her what was wrong. I would always ask if she was okay. Her answer was exactly the same every time:

“I’m brushing my teeth.”

This is the first time I remember knowing I was being lied to. At night I would hold up my toothbrush, inspecting it carefully. First, to attempt to figure out how it could make my mother make those sounds. And second, to make sure it didn’t have blood on it.

Sometimes, in her post-purge haze, my mother would grab my toothbrush instead of hers to clean up. Sometimes, I would go to brush my teeth before school and find that it was already damp and had a peculiar, sour taste.

My mother had suffered from anorexia nervosa since she was a teenager. Without going into too much detail, in order to respect the privacy of many people who are still alive, her childhood was not a good one. After her grandmother passed away, her one true solace in a world of cruelty, her eating disorder appeared. It comforted her. It gave her control. It calmed her frayed nerves. The chemical shifts in her brain made her feel that she could survive. And she did—she held on.

When she was in her early twenties, about the age that I am now, actually, she met my father. He was divorced, quiet, hard working. They got married. She was actively bulimic at this point, and had been for about five or six years. I don’t think my father knew, or if he did, he didn’t understand it.

She stopped menstruating shortly thereafter. She was five feet five inches tall and weighed somewhere in the mid-eighties in pounds. Her doctor told her she wasn’t going to be able to get pregnant. I don’t think that disappointed her, and with her doctor’s blessing, she stopped taking birth control pills.

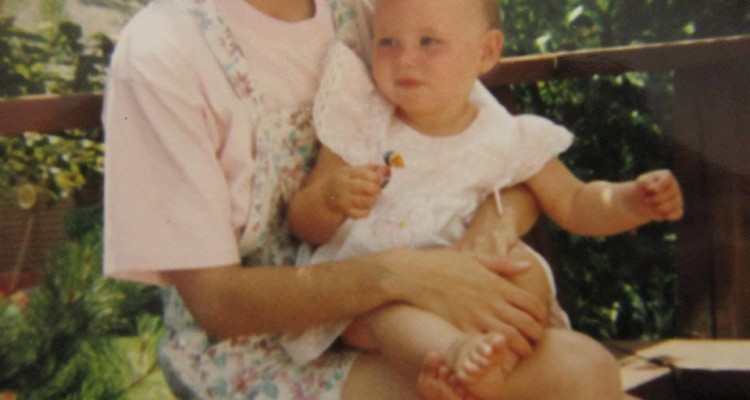

But she did get pregnant. She gave birth to me when she was twenty four years old. After my birth, she was sick. Her body hadn’t been ready to nourish a child when it was hardly nourishing itself. She was worn out. I was a fussy baby with colic who she didn’t understand and struggled to bond with. For the first few weeks of my life, my father was my primary caregiver. I guess it all fell apart when he finally went back to work.

By the time I started school, my mother’s bulimia was a normal part of my life. But as I grew, her focus on my looks and her fears weighed heavily on me. It would take me years to figure out that it was never about me at all.

Anorexia is hardly ever actually about weight

My mother was an addict. There were kids I went to school with whose parents were alcoholics, drug addicts and gamblers. Whatever the poison, these people all had one thing in common with my mother: they needed their fix and would get it, whatever the cost.

Mum was addicted to the “high” she would get from purging whatever food she consumed. Subsequently, she was addicted to the “high” of early-starvation. Not everyone will experience this high, but if you do, you know what I’m talking about. Brain chemistry has a lot to do with it, and when that internal systematic flaw meets the right environment, addiction is born.

As a child, though, I didn’t understand this. I grew to resent my mother because of her addiction. Whenever I would get sick, with a stomach bug or anything else that would make me vomit, her disgust was palpable. By the time I was ten years old, I had developed a debilitating fear of vomiting (called Emetophobia) that persists to this day. I am also plagued with flashbacks to the sounds and smells of my childhood. I figured out several years ago, during an acute illness, that I too share my mother’s “high” from starvation and vomiting.

Now, I am terrified of throwing up because it makes me feel amazing and I don’t want to end up like her: addicted to it.

When I was twelve years old, my parents decided to let me go to overnight summer camp. This was extremely odd to me, because my mother’s need to control me (because of her illness) made her much too nervous to let me out of her sight for extended periods. I knew that something big was happening. For months leading up to this decision, my mother had become extremely sick. I started to wish for her death, because I couldn’t stand watching her suffer anymore. And I was suffering too. She would ask me to rub her back, and I would recoil as I lifted her nightgown up and exposed the sharp bones of her back, her ribcage. I could see her organs pulsating just under her skin. She was absolutely skeletal.

I remember as a little girl, maybe of four or five, having a recurring nightmare for several years that would scare me so much I would wake up and have to run to the bathroom, lest I soil myself in fear. In the dream, I was being chased by a skeleton. For years, I was petrified of Halloween decorations for this very reason. Skulls horrified me. Bones made my heart race. Eventually, the dream went away, but several years later, when my mother went into the hospital to die, the dream came back. I realized then that she was the skeleton. And that she had never stopped terrifying me in my waking life.

While I was at sleep away camp, my mother went into the hospital. She weighed fifty-eight pounds. I was twelve years old and I weighed more than my mother. I went to summer camp and sang songs around the campfire while my mother spent months in a bed with a feeding tube. Doctors couldn’t understand how she was still alive. When I came back, I was told that she was dying. I should prepare myself.

What no one understood was that I had been ready for years. I had known my mother would die for a very long time. I was ready. In fact, I think I wanted it. I imagined at that point that she did too.

One of the only times my mother and I did anything together was when she and my grandmother took me to a Sarah McLachlan concert. My mother only wanted to hear her sing one song, then she was going to leave because she hated large crowds. She left the auditorium after she sang Angel.

Spend all your time waiting

for that second chance

for a break that would make it okay

there’s always some reason

to feel not good enough

and it’s hard at the end of the day

I need some distraction

Oh, beautiful release

memories seep from my veins

let me be empty

and weightless and maybe

I’ll find some peace tonight.

But my mother didn’t die.

By the time my mother got out of the hospital, I had left home. I was twelve years old. That, though, is part of my story. And this is about Mum.

I continued to grow and change. I got my period. I needed a bra. I figured out how to masturbate, wondered what sex would feel like, tried to get boys to kiss me and hold my hand when we went to the movies. I watched my body grow and change; there was hair, curvy flesh; a whole new body.

But my mother stayed the same. She stayed gaunt and thin forever. Her hair thinned, her face grew long and weary, her eyes were sunken and she always looked exhausted. The changes my body were going through must of terrified her. Because she had really arrested her own development decades before. She had remained in a childlike body. I, her only daughter, was turning into a woman.

MY MUM IS STILL ALIVE. She lives a quiet and solitary life because her days are filled with a lot of pain. She doesn’t leave the house much. She has the companionship of my younger brother and mountains of books. She is very smart and funny, despite her illness. She no longer purges, but she is still very much emaciated and her body has withstood years and years of abuse. She has to do an enema every day, because her body can no longer have a bowel movement on its own. She hasn’t seen a doctor in a long time. But she calls me and I make her feel less scared when something goes wrong in her body.

I tell her it will be okay.

The truth is, her eating disorder took her away from me years before I was born. It robbed me of the security of a mother, the friendship a girl can have, the role model. She became an example of what I should fear. Still, even as a little girl, I felt that I needed to protect her from the world; a world that had cracked her open and taken out her soul. A world that was so hateful that it made her need to hang her head over the toilet and vomit until she was hoarse and doubled over in pain— just to make it through the day.

I eventually learned that it wasn’t the whole world; it was just Mum’s world. I didn’t have to live like that. I didn’t have to be afraid. The world was going to be good to me.

And for the most part, in spite of everything, it has been.

I am a grown woman now. I talk to my mother on the phone a few times a week. Sometimes we talk about her eating disorder. Sometimes we don’t. I have come to see my mother has a human being. She isn’t so much “my mother” or “my friend” as she is this person who is in my life who has suffered greatly and still manages to find things in life that are good.

She loves to read the obituaries in the paper. She is fascinated by other people’s lives. It reminds me of how, when I was twelve and an aspiring writer, I drafted her obituary obsessively. I didn’t want to expose her, I just wanted her to finally have some peace.

Someday, no doubt, I will need to write that obituary. I’m not sure what I will say now. Her death will come, at least in part, from her eating disorder. Her heart might just stop beating one day. I don’t think I will say that she died from anorexia, though. I won’t say that her bulimia ravened her body for over thirty years. I won’t say that she died of addiction or sadness.

I might just say that she died. I hope I can add, surrounded by family.